Analysing the future

In the 1960s, systems theorist Herman Kahn developed the first analytical studies of the future for the US Government. The American-dominated field of future studies had an ear with the US government on the highest levels and was soon invited to the executive meetings of multi-national companies. The popularity of the field was further fuelled by the best-selling authors and futurists John Nasbitt and Alvin Toffler, who reached a status as professional gurus.

An important moment in the recognition of future studies occurred during the oil crisis in the 1970s, when the Dutch energy company, Shell, used scenario planning to deal with the crisis. Future studies developed a comprehensive repository of methods and tools for various purposes and settings, which was readily absorbed by companies, who at the time were developing market strategy as a core competence. Since then, foresight and strategic planning have been key elements of the management of multi-national companies.

Corporate foresight

“Foresight is the process of developing a range of views of possible ways in which the future could develop, and understanding these sufficiently well to be able to decide what decisions can be taken today to create the best possible tomorrow.” (Horton 1999, p.5)

Since the 1980s the future studies community has been in a crisis – mainly due to its own success. In a 2006 survey, it was found that 60% of top management in European companies regularly participate in foresight (Norman & Draper 1986). Mahaffie (2003, p.4) states that “The need for longer term thinking is recognized nearly everywhere”. The problem is that people bring foresight into organisations without ever realizing that they are working as futurists. In other words, the popularity and diffusion of futures thinking into corporations have made the field itself superfluous. In addition, the rapid and uncontrolled growth of future studies has made the community fragmented; without an ongoing renewal of the ageing tool kit, professionals have had nothing new to come back for (Hines 2003).

The future methods and tools have not only been adopted at the strategic levels of corporations – know as Corporate Foresight – but have also been integrated in a number of other disciplines. Scenario planning, in particular, is a widely acknowledged method, and Hines (2003, p.21) observes that “Futures in the organizational context has been slowly re-appearing, but in non-traditional places, such as market research and new business development”.

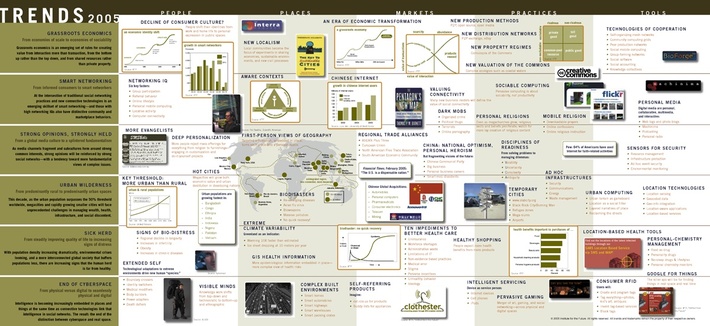

There are still pockets of traditional futurists embedded in think-tanks, but their influence is far from what it used to be. The Institute For The Future in California is one of the surviving dinosaurs that has managed to renew itself in the past 40 years and continues to publish reports on a regular basis.

The futures field concentrates on general society, markets and global factors, so it does not produce tangible future concepts. On the other hand, future methodologies have been instrumental in creating a foundation for futures thinking across a range of disciplines and is widely used for developing futures concepts.

Trend research

In the late 1970s marketing departments increasingly used market research to support their business strategy. This marked a first step in a gradual re-orientation of a company’s core competence from strategy and markets to innovation and users. In succession followed a new industry of trend research which used methods from futures research and sociology to predict markets and lifestyles. The specialized trend agencies typically predicted up-and-coming lifestyle trends and presented them to clients through magazines, biannual events or exclusive, custom-made presentations for selected clients. Today there are several websites which accumulate the latest from around the world with the help of thousands of trend-scouts.

The time horizon of trend research is normally 6-18 months, but some industries, e.g. the automotive industry, require a longer perspective and look as far as five to ten years ahead. A typical trend forecast consists of 5-15 general trends in lifestyle or technology, which are communicated to the client company’s marketing and R&D department. The R&D department then seek to understand how these trends may affect the business area of the company and develop concepts for future innovations to take advantage of these trends.

User innovation

During the 1980s and 1990s globalization had a profound effect on the way business is done around the world. The change has been driven by global trade agreements, the Chinese ‘open door’ policy, and advances in information technology. Around the world geographical, technical, political and cultural barriers are eroding and the effect is felt even in the most isolated areas.

Companies are now facing tougher competition than ever before in markets that are increasingly complex and volatile, but also full of new opportunities. Business leaders and politicians agree that innovation is the only way for companies to maintain competitiveness and profitability, such that “innovation has become the industrial religion of the late 20th century” (Valery 1999, p.5). The increased focus on product innovation – particularly user-oriented innovation – shifted the balances in companies, so that the R&D department, which previously followed orders from above, became the key to the company’s survival.

Skunkworks

Demands for a continuous flow of high-level innovations led to a restructuring of R&D to facilitate out-of-the-box innovation. Multi-disciplinary teams with a mix of engineers, industrial designers, ethnographers and sociologists became commonplace in most companies and trend research was a central factor in the pursuit of new innovation. As a preliminary step in the search for radical innovation, many major companies conduct conceptual vision or future projects to inspire their research and development, but also to provide a window for early interaction with consumers, so that new products will have a higher success rate.

For some companies the idea of specialized, forward-looking research units was old news. In the 1960s the invention of microchips led, as with other new technologies, to an exploration of how they could transform the world and the kind of value propositions that the technology could offer. For example, in 1967 the Philco-Ford Company released a series of short films titled 1999 A.D. One clip shows online shopping and predicts that all paper work is done online. There are no keyboards, but a row of buttons facilitate interaction. Another clip showcases an intelligent and automated kitchen for maximized health.

It was widely assumed that the computer would make offices paperless by 1990. For Xerox, which made a living of selling copying machines, it was an alarming prospect. In 1970 Xerox created the Palo Alto Research Centre (PARC), near Stanford University, to explore the possibilities of the new technology and hopefully lead Xerox to dominate the office of the future. PARC was financially well-funded and soon became a haven for scientists, engineers and cognitive psychologists. Among others, PARC invented the computer mouse, laser printer and desktop-style computer interface which continues to dominate offices 40 years later.

The intensive and creative research units, with their mix of scientists, specialists and artists, were quickly recognized as a powerful incubator of new ideas. It was popularly named a ‘skunkwork’ because of the secrecy around their works. In the mid 1970s the word entered the business jargon (Sibbet 1997).

A skunkwork is often accompanied by a laboratory with a home-like setting in which test subjects can come and live for days or weeks and try out new solutions, while researchers observe them. The European Living Network is a partly EU-funded organisation which coordinates many such laboratory projects on European ground. On American soil Microsoft, HP and others opened in 2008 the Innovations Dream Home at Disneyland with the aim of showing how technology can create a fun and interactive environment for people’s lives.

The skunkwork’s object of investigation has changed over time. Until the end of the 1980s, the focus was on micro-chips and their significance for ‘the office of the future’. In the 1990s, ambient technologies and the market orientation towards consumers entailed investigations into ‘the home of the future’. Since the turn of the century mobile communication and social networking have held the promise of the future. As one might expect, leading telecommunication companies like Ericsson, Nokia, AT&T and Skype have shown future concepts in the past few years.

The concepts coming from the skunkworks are typically exhibited in popular magazines (Wired), trade-fairs (CES of Las Vegas) and festivals (Aarts Electronica), where technology specialists gather and show off their cutting-edge concepts.

Concept art

Companies whose expertise is within more traditional technological domains also have to innovate and find new ways to bring new value to their customers. One way is to arrange design competitions to inspire new product development, connect with trendsetters and pick-out the best candidates for employment.

Design competitions are not a new phenomenon, but in recent years they have generated increasingly valued innovation and out-the-box concepts. In some instances the theme of the competition is framed in the future, but it is not required to follow an analytical approach, so it is commonly interpreted as just another way to encourage participants to envision a completely new context with no strings attached. Braun and Electrolux are some of prominent companies that organize competitions and award prizes.

The divisions between design, innovation and future visions are seamless, so in the international design competitions and awards, it is possible to find a mix of all three categories (Bosch prize and Red dot Award, IDSA awards). However, over the past two decades there has clearly been a shift towards more radical innovation.

At the intersection of concept and future design, The School of Design at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand has a programme dedicated to Design Led Futures. It has been running since 2004, and is one of the few educational programs dedicated to holistic future scenarios. The purpose is to encourage an open and free discussion about how people wish to live in the future. Each year is sponsored by a particular company which, in return, becomes the subject of the students’ projects.

Extract from PhD thesis “Everyday-Oriented Innovation”