The potential of digital tools to empower critical investigation

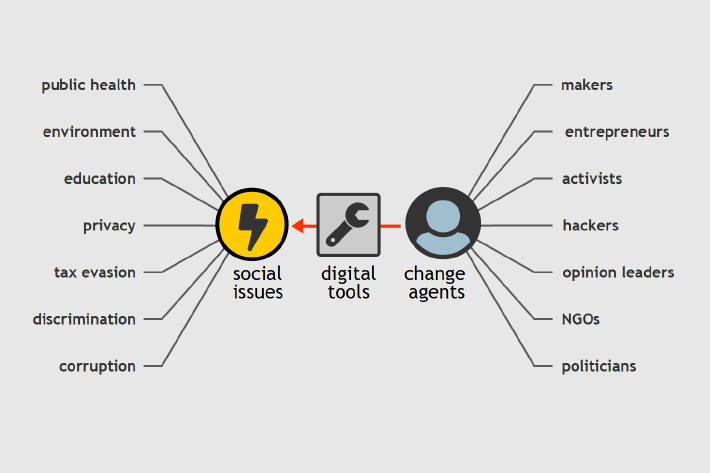

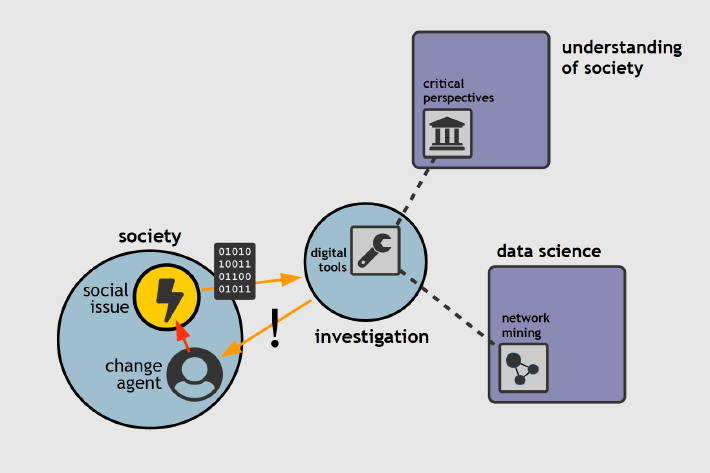

This blog post is about my main field of interest: the development of digital tools for critical investigation of social issues. I believe it is an important topic because it seems to me that the complexity of modern society has made it difficult for people around the world to deal with many fundamental social issues.

Fortunately, it is also my conviction that a number of factors are coming together these years to make it possible to develop digital tools that can give us insight into the workings of society like never before, – and thereby make it possible to better handle those issues.

Before I go into explaining the potential that I see for developing powerful digital tools, I will talk about what I see as characteristic for modern issues and the challenges it poses for those who deal with them.

Complex social issues

One of the most striking characteristics of today’s issues is the number of stakeholders that are involved and the complexity that arises when they have very different interests. The list of stakeholders will often include businesses, NGOs, public institutions, consumer groups, engaged citizens and political action groups from different sectors and across national borders.

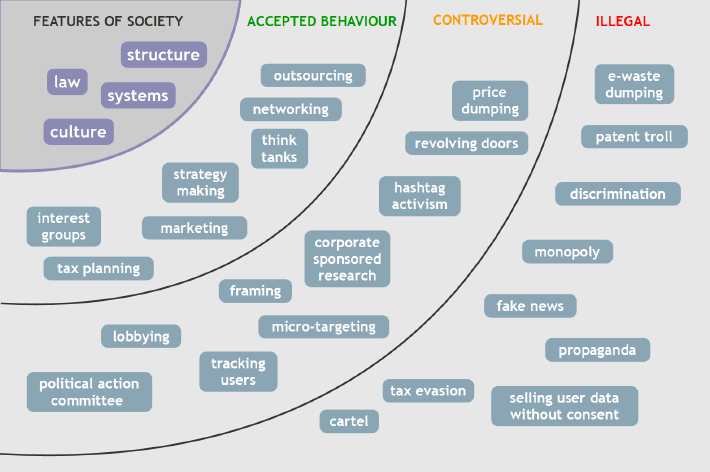

However, it is not only the number and diversity of stakeholders that is daunting. Stakeholders may also make use of sophisticated strategies and schemes to increase their influence. The schemes may take many forms and the acting party will often try to keep it undercover so they can derive the most benefit from it.

The American Koch brothers is a textbook example of all the different schemes that may be employed. They have a strong economic interest in the continuation of a carbon-based energy production, so in order to limit restrictions on their businesses, they financially support a wide range of people and organisations – from media manipulators, think tanks and astroturf agents to courtrooms, politicians and scientific researchers. The Koch brothers are an extreme case, but the same schemes are often employed on a smaller scale whenever there is a stakeholder who has a strong economic interest.

Challenges of investigation

These kinds of connections are not easily exposed because they often express themselves through intertwined relationships, formal or informal, and involves the exchanges of a wide variety of resources and services over time, so despite the behaviour being controversial and sometimes illegal, it usually goes undetected.

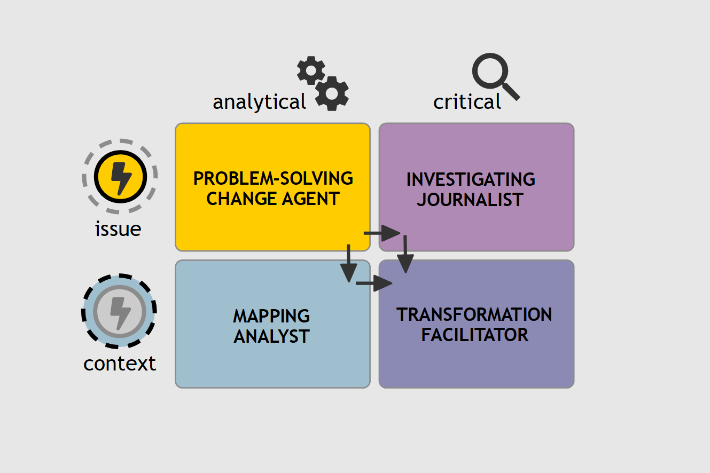

Change agents do not have the resource and expertise to uncover the underlying forces that may be operating under the surface, so investigators play an important role in exposing them. But even so, it is far from a straightforward task cause the situation is seldom as clear-cut as with the Koch brothers, and there may be legitimate reasons for the behaviour of the involved parties.

Companies are for example allowed to sponsor research institutions and donate to political parties, so it can be very hard to prove that supposedly independent researchers and politicians changed their opinions because of the money they received.

In some cases, the transition from accepted to non-accepted behaviour can also be very smooth. For example, when companies started selling digitally connected products, it was natural for them to use the new technical capabilities to collect as much data about their users as possible to optimize sales. It was not until later that citizens would voice their concern about infringements on privacy and rules were introduced to limit the collection and selling of private data.

There are even greater challenges for those investigators who aim at the root cause of the issues and seek to change the laws, social structures, technological systems and cultures that govern the issues. With regard to tax evasion, it would, for example, mean that the objective was not so much to bring to justice any individuals that have made illegal dispositions, but rather to change the international financial system that enables such malpractice.

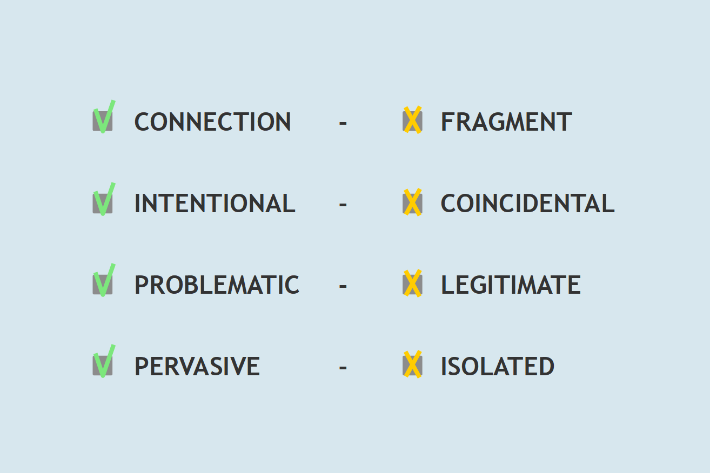

For this kind of approach to be successful it has to be shown that there is a pervasive problem and it is not just an isolated incident, so it requires a broad and fine-grained investigation to collect sufficient evidence. In this way, it resembles the challenges of analysts when they analyse and map market sectors or consumer domains.

The extent of such investigation is naturally too demanding for independent ‘lone-wolf’ investigators or analysts and requires somebody to take the role as ‘transformation facilitator’ to coordinate the efforts between collaborators and ensure perseverance over time.

In general, transformative endeavours do not only face the challenges of ordinary investigations, i.e. identifying an intentional behaviour and making a convincing case that it is problematic, but also the challenge of mapping the behaviour more broadly to show that it is a pervasive problem.

Stated in more technical terms, it is essential for change agents, investigators, analysts and facilitators to find relational patterns in data. Depending on their general objectives they face challenges in different degrees, ranging from finding a simple relation between two entities to proving that behavioural pattern is repeated by an individual or by a significant part of a population.

New sources of data

These challenges would have been insurmountable in earlier times, but in an interesting turn of events, the same information technologies that facilitate a much more complex interaction in society, also makes it possible to analyse and manage it.

One of the key factors is the availability of data and the relative ease with which we can access to data. The web is today a rich source of all kinds of knowledge and popular demand for open data has given access to extensive public records. Data leaks have furthermore given access to data about some of the most secretive aspects of modern society.

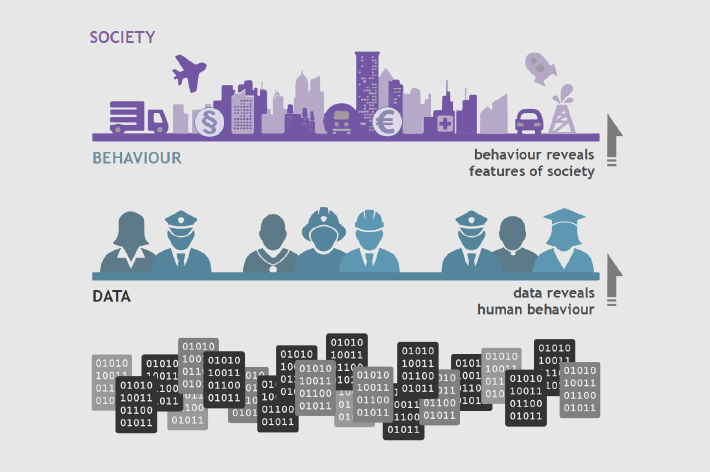

But the best may not be the availability of factual data. The popularity of social media and blogs have established a high bandwidth connection to many peoples lives, feelings and thoughts, which allows us to extract high-level conceptual insights. It also allows us to analyse human behaviour in both detail and the big picture, so it is possible to make connections between the features of society and individual behaviour.

In union, all these data sources provide a fertile ground for exploring patterns in data and identify behaviours. In the following, we will look at the data science workflow that may bring it to fruition.

Basic data science workflow

In order to evaluate the feasibility of developing powerful digital tools for critical investigation, I will briefly go through a basic workflow and the already existing technologies that may serve as a starting point.

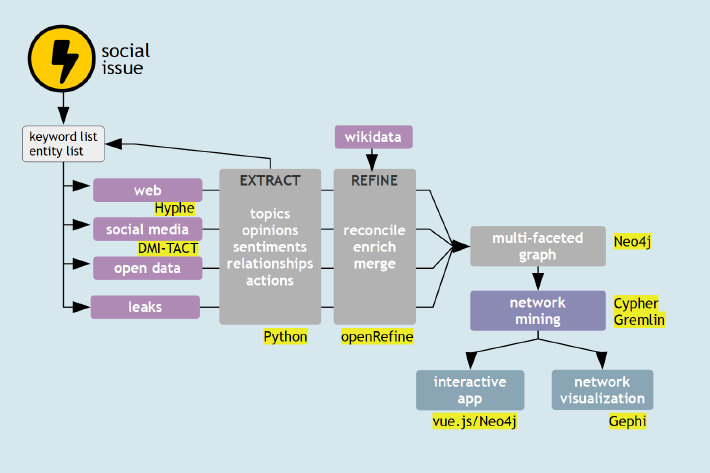

The workflow starts with a question or an issue which guides the collection of data. Social issues are usually quite diverse and require therefore several different types of data to be gathered. Many popular web services offer an API to access parts of their data, but it is of course also possible to use more rudimentary ways of scraping data, – if you are not able to just download the dataset from an online repository.

Each of these sources goes then through a process of extraction and refinement before they are merged into one multi-faceted graph. The various tasks involved in these processes have been developed over many years and have today reached a stage where powerful machine learning algorithms can be leveraged with fairly simple code, and confidently extract the main elements of text and images, such as entities, actions, topics, opinions, sentiments etc.

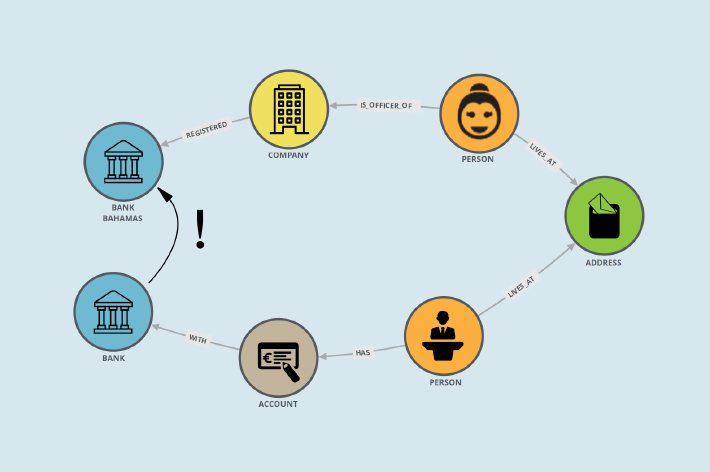

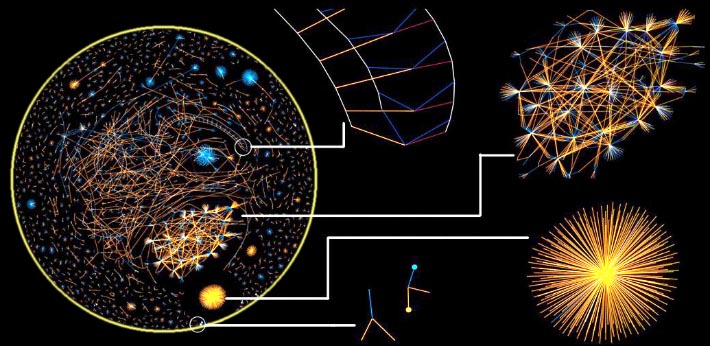

The different graphs are then merged into a Neo4j graph database. Neo4j is currently the industry standard for storing and accessing relational data, however in the context of small-scale investigation it is not so much the technical performance of the database that makes it attractive for investigators, but rather the visual interface and the intuitive cypher query language that empower users to easily merge data and perform advanced network mining.

The end result is a multi-faceted graph containing relations between all kinds of stakeholders intertwined with behavioural and semantic information, – such as the places they visit, the laws they underwrite, the opinions they express etc.

Once the exploration of the network is concluded, there are several solutions available for presenting your results depending on the ensuing user scenarios. If you want to display a static network, Gephi provides ample features to layout and enhance the graphical representation. If you, on the other hand, want the users to interact with the resulting network you have the choice between using Linkurious’ app or you can custom-tailor your own browser app with vue.js or a stand-alone app with Electron. From May 2018 it may also be possible to build native Neo4j apps.

This brief explanation of the overall workflow for exploring relational data should first and foremost convey the message that there is today a wide spectrum of very capable technologies that can support the full process from start to end. In the following, we will look further into the “network mining” phase, where the all-important exploration of complex patterns takes place, and I believe there is a particularly strong potential for improving the quality of the process.

Mining networks

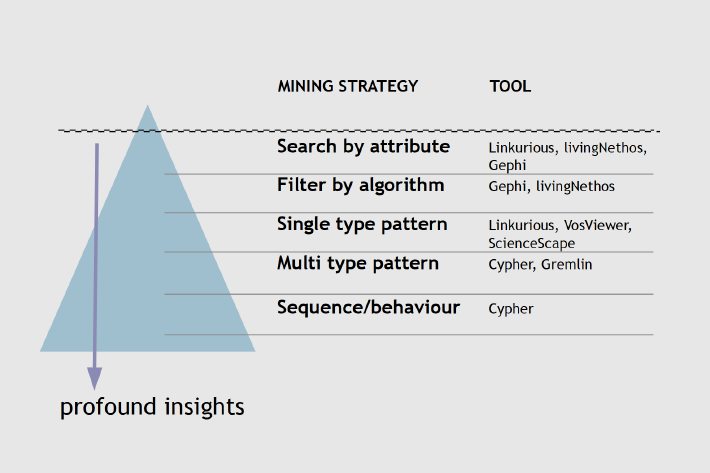

A graph may be searched in many different ways. As a start, you may search for a particular stakeholder (e.g. a company director) or occurrences of a word (e.g. ‘bribe’). You may also search for the shortest path between two people and thereby drastically reduce the results that the query returns. However, these methods require a preliminary intuition and do not easily lead to the identification of previously unknown entities or intriguing structures in the network.

To exploit more fully the insight that may be hiding in a multi-faceted graph, it is necessary to look for relational patterns in the graph. You could, for example, investigate where researchers that publish climate sceptical blog post, get their research funding from or check if researchers of public research departments suspiciously migrate to and from positions in companies with a clear interest in the field. There are many possible patterns to explore in the relations between social, behavioural and semantic elements, so the results depend to a large degree on the inspiration of the investigator.

You can also programmatically search for unusual patterns in the whole graph. It is already common practice to apply different algorithms to a single graph to identify key influencers and people bridging different communities, but in a multi-graph, there are multiple types of elements, so it comes with its own powerful possibilities and complex challenges, and there is little research in this field at the present moment.

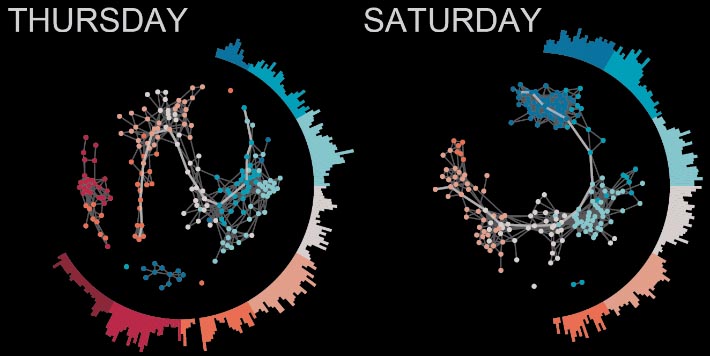

Another interesting way of identifying anomalies is to look at behavioural patterns. This approach has among other been used in the context of Russian trolls, credit card fraud and financial trading, where the main objective is to identify users with suspicious behaviour. The problem in this field used to be that if you look at individual transaction it is almost impossible to make a distinction between different types of users. By visualizing behavioural patterns over time, it was made possible to identify the culprits in a blink of an eye.

In conclusion, it is interesting to note that even though network analysis has been around for several decades, it is not until quite recently that multi-type pattern and behavioural discovery strategies have been introduced, and even so only by a small group of cutting-edge researchers and investigators. It seems, therefore, to be a field in the making with lots of potential for further progress.

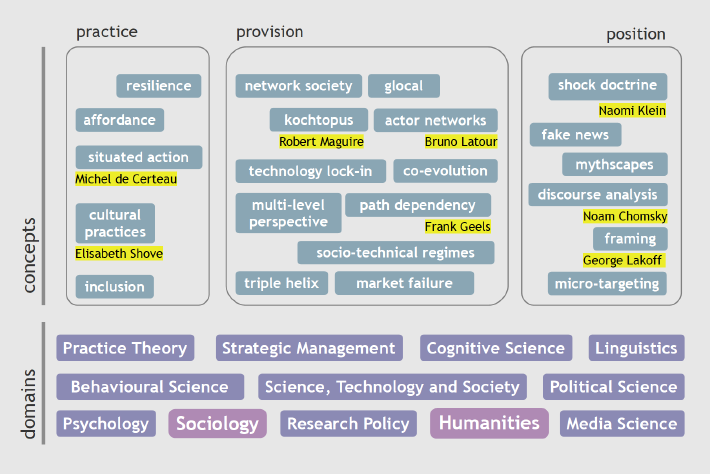

Critical perspectives

I have so far emphasized the new possibilities for critically investigating society that come with access to many types of data and advancements in data science. However, I do not want to overstate the virtues of these developments. An algorithm can only process the data you provide, in the ways you specify. The output may inspire new lines of investigation, but it will not on its own suggest to include other types of data and process it in new ways. It remains therefore essential for an investigator to have an inspiration for what behaviours or ‘schemes’ to look for and be able to translate it into concrete network mining techniques.

The schemes may, for example, concern how blockchain currency is used in for bribery, how the use of particular words can cause certain reactions among subcultures, or more fundamentally how social systems cause people and companies to act in certain ways.

Because new types of schemes emerge as society evolves, it is an on-going challenge for investigators to have a relevant repertoire of critical perspectives and schemes to inspire their line of enquiry.

Academics have for many decades strived to spearhead our understanding of society, so it would be reasonable to think that the field of critical investigation and an academic researcher could learn a lot from each other, but to my knowledge, there has not been much of a tradition of collaboration between the two. I believe, nevertheless, that things may be changing now that academics are facing calls to be more relevant for society and digital tools empower investigators to dig deeper into the workings of modern society. In any case, it seems certain to say that there for many years to come will be plenty of work to do for those who are up for the challenge to translate academic concepts into practical digital tools.

Conclusion

The purpose of this presentation has been to show that there is great potential for developing digital tools to critically investigate social issues. In order to first understand the importance of the topic, I explained that social issues are becoming more complex, so to be able to deal with them you will have to be capable of analysing intertwined networks of people, organisations and their actions.

I then presented a number of factors that I believe as a whole will make it possible to develop powerful new digital tools that can aid investigators to unravel the complexity of modern society. Herein, I first emphasized the value of the on-going digitalization of all kinds of activities in our society and the maturity of related data science workflows as a strong foundation for developing new tools.

Finally, I described some novel network mining strategies and argued that they in combination with critical perspectives from academia will make it possible to significantly enhance our understanding of modern society and thereby deal with important social issues.