Early inventions and visions

The history of radical concepts started with architects. They have for several centuries been proposing grand visions of how to organise cities, create lively communities, comfortable housing, efficient work-places and improve people’s everyday life. The strong bonds between the arts and architecture have fueled intellectual debates and well into the 20th century they have dominated the field of innovation.

Houses are built to live in, and not to look on.

The utopian visions drew for the first time a wider attention when Thomas More published Utopia in 1516. Herein he introduced a provocative and novel view on architecture by stating: “Houses are built to live in, and not to look on”. About the same time Leonardo de Vinci sketched several future products, such as the helicopter, the parachute, the submarine and the car. It was not until 300 years later that his ideas were improved upon.

The re-construction of Barcelona in the 1850s is an example of one of the first implementations of an architectural master plan with a humanistic approach. The plan built on an analysis of working-class conditions of the time and focused on people’s need for sunlight and greenery in the surroundings, as well as natural lightning and ventilation inside their homes. Streets were optimized to accommodate pedestrians and assure a seamless flow of people, goods, energy, and information. Even though entrepreneurs over the years have overruled some of the good intentions of the re-construction, Barcelona remains one of the most livable mega-cities of the world.

Hand in hand with the industrial revolution emerged the field of design and new ideas about manufacture and products. The first public exhibition was organised by the Royal Society of Arts in London during 1756, where prizes were offered in various categories. This was followed by exhibitions in France, the United States, Italy and other industrialized nations. In 1851 the first international exhibition was held with the title: ‘The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’. The exhibition has been repeated ever since, but changed its name to ‘World Fair’ and later to ‘Expo’. Until 1938 these expositions focused on trade and were famous for the technological inventions on display (Wikipedia contributors 2010). A major attraction of each Expo is the building raised to host the exhibition. They are made by state-of-the-art building materials and techniques, and are designed by the world’s most renowned architects. Many of the earlier buildings stand today as guideposts for future, which have not arrived yet (Kihlstedt 1986).

The Futurist Manifesto from 1909 marked a high point in an unlimited idealization of technology and love for “speed, aggression, human masses, patriotism, militarism, war” (Kruft 1994, p.403). However, the two world wars effectively set a stop to the most extreme expressions of futurism.

Social critic

The moral worth of an action is determined by its outcome.

Not everyone shared the mainstream architects’ and engineers’ visions of a wonderful new world based on technological progress. There were groups of industrial designers that were critical of technological progress as early as the mid-19th century. In those days the design profession did not have the same legacy as architecture, and their responsibilities were confined to superficial decoration of the industrial products that engineers had developed. Nevertheless, groups of socially conscious designers emerged, when the negative social consequences of the new modes of production became apparent. In a counter-offensive to the Industrial Revolution it was proposed that the arts and crafts production mode should be re-established to improve the living conditions of workers and hold at bay the aesthetically impoverished industrial design. It was about the same time in history that John Stuart Mill formulated a philosophy of utilitarianism, stating that the moral worth of an action is determined by its outcome, which gave legitimation to the critical movement. This marked the beginning of functionalism and the decline of historical formalism.

Socially conscious architects and designers worked closely together. For example, Le Corbusier and others prominent architects sought to unify the design of the house itself right down to the teaspoon with the participation of the tenants in a building named the Weissenhof Estate (1927). The goal was to offer a utilitarian design and was advertised as a blueprint for the future workers’ home.

A criticism of the dehumanizing effects of the machine was also voiced by the comedian Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (1936) and later by Jacques Tati in Mon Uncle (1958). Many writers and filmmakers have portrayed technology as an evil for society. Some of the earliest and best known were filmmaker Fritz Lang in Metropolis (1927) and writer George Orwell with 1984 (1949).

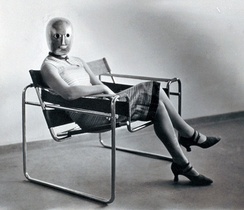

Well into the 1960s, the socially responsible and functional approaches to design were further elaborated by the Bauhaus and School of Ulm. They proposed that the investigation of the objective and scientific conditions of design can bring about democratic change in society. The field of social design created a strong conceptual and methodological foundation for designing strong, value-based visions of everyday life, but as in architecture, it was not based on an analytical approach to seeing into the future.

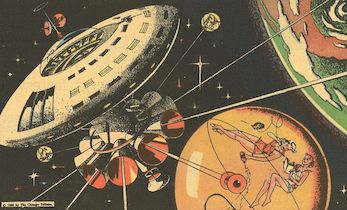

Post-war optimism

After the second world war, new materials and space travel fueled imaginations of the 1950s and 1960s. A positivist technological visual language emerged with Luigi Colani and Verner Panton, who took advantage of the new freedom offered by plastic to make curvaceous and emotional designs.

After 1957 Disneyland, in California, offered a tour of the Home of the Future (Horrigan 1986). The attraction was sponsored by Monsanto Company and engineered in collaboration with MIT. The fiberglass house featured household appliances such as microwave ovens and was set in a fictional 1989. In the first six weeks it was seen by over 435.000 visitors. A second era of world expositions started with the Building The World of Tomorrow exposition in New York in 1939. The new optimistic futuristic epoch focused on cultural significance and global issues of humanity. In light of the cross-cultural dialogue and exchange of solutions that defined the Expos, the exhibitions became an excellent opportunity for companies to present consumer goods.

For the Brussels World Exhibition of 1958 Philips made a prominent exploration into the future, called the Poéme Électronique. The event was designed by a trio of composers and architects including the famous Le Corbusier. The exploration was followed up by a presentation in 1964 of The Home of 1975 (Marzano 2006), that promoted a more integrated use of electrical equipment in the home. In the same period Philips employed the industrial designer Syd Mead to work for their creative ‘wildcats team’. Since the 1970s Syd Mead’s vehicle designs have been an important feature of many science fiction movies and computer games.

The glorification of technology and the future can also be recognized in the concept of a Walking City (1964) by architect group Archigram and in Peter Cook’s later biomorph Kunsthaus (2004) in Graz. The latter is commonly referred to as the ‘friendly alien’ and has a light emitting outer skin which enables it to communicate with the surrounding city.

Extract from PhD thesis “Everyday-Oriented Innovation”